[This is taken from James MacCaffrey's History of the Catholic Church, which appears in its entirety on this website.]

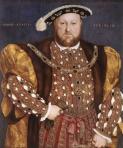

The accession of Henry VIII. (1509-47) was hailed with joy by all

classes in England. Young, handsome, well-developed both in mind and

body, fond of outdoor games and amusements, affable and generous with

whomsoever he came into contact, he was to all appearances qualified

perfectly for the high office to which he had succeeded. With the

exception of Empson and Dudley, who were sacrificed for their share in

the execution of his father, most of the old advisers were retained at

the royal court; but the chief confidants on whose advice he relied

principally were his Chancellor Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury and

Lord Chancellor of England, Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester and Lord

Privy Seal, and Thomas Howard, afterwards Duke of Norfolk, Lord

Treasurer of the kingdom. Soon, however, these trusted and loyal

advisers were obliged to make way for a young and rising

ecclesiastical courtier, Thomas Wolsey (1471-1530), who for close

on twenty years retained the first place in the affections of his

sovereign and the chief voice in the direction of English affairs. As

a youth, Wolsey's marvelous abilities astonished his teachers at

Magdalen College, where the boy bachelor, as he was called because he

obtained the B.A. degree at the age of fifteen, was regarded as a

prodigy. As a young man he was pushed forward by his patrons, the

Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Winchester, and won favor

at court by the successful accomplishment of a delicate mission

entrusted to him by Henry VII., till at last in 1511 he was honored

by a seat in the privy council. New dignities were heaped upon him by

Pope and sovereign in turn. He was appointed Bishop of Lincoln and

Archbishop of York (1514), was created a cardinal of the Roman Church

(1515), and in a short time he accepted the offices of Lord Chancellor

and papal legate for England. If he did not succeed in reaching the

papal throne, a dignity to which he was induced to aspire by the

promise of Charles V., his position as legate made him at least

virtual head of the English Church. Instead of being annoyed, Henry

VIII. was delighted at the honors showered upon his Lord Chancellor

by the Roman court. With Wolsey as his obedient minister and at the

same time an ecclesiastical dictator, he felt that he had more

authority in ecclesiastical affairs than was granted to Francis I. by

the Concordat of 1516, and, though possibly at the time he did not

advert to it, he was thus preparing the way for exercising in his own

name the control that he had exercised for years through his chief

minister in the name of the Pope.

The dream of reconquering the English possessions in France induced

Henry VIII., during the early years of his reign, to side with the

Emperor Maximilian and Ferdinand of Spain against Louis XII.; but the

comparative failure of the expeditions undertaken against France, the

resentment of the people who were burdened with taxation, and the

advice of Cardinal Wolsey, led him to forego his schemes of conquest

for a time in favor of a policy of neutrality. The election of

Charles V. in 1519 changed the whole aspect of affairs on the

Continent, and raised new hopes both in the minds of Henry VIII. and

of his faithful minister. An alliance with Charles V. might mean for

England the complete subjugation of France, and for Cardinal Wolsey

the votes of the cardinals at the approaching conclave. While

pretending to act the part of mediator between the rival sovereigns,

Henry concluded a secret alliance with the Emperor in 1521, and

prepared to make war on France. The failure of the forces dispatched

under the Earl of Surrey, the disappointment of Wolsey when he found

himself deceived by Charles V. at the conclaves of 1521 and 1523, and

the outcry raised in Parliament and throughout the country against the

French war, induced Henry VIII. to reconsider his foreign policy. The

defeat and capture of Francis I. at Pavia (1525) placed France at the

mercy of the Emperor, and made it necessary for Henry to come to the

relief of his old enemy unless he wished to see England sink to the

level of an imperial province. Overtures for peace were made to

France, and in April 1527 Grammont, Bishop of Tarbes, arrived in

England to discuss the terms of an alliance. The position of Cardinal

Wolsey, which had been rendered critical by the hatred of the nobles,

who resented his rule as the rule of an upstart, and by the enmity of

the people, who regarded him as the author of the French war and of

the increased taxation, was now threatened seriously by the public

discussion of difficulties that had arisen in the mind of the king

regarding the validity of his marriage.

The Lutheran movement that broke out in Germany two years after

Cardinal Wolsey's acceptance of the twofold office of papal legate and

royal chancellor, found little favor in England. Here and there, at

Oxford, at Cambridge, and in London, individuals were found to

subscribe to portion of Luther's programme; but the great body of the

people remained unmoved by the tirades of the German reformers against

Rome. Henry VIII., whose attention to religion was noted as one of his

characteristics by the observant Ambassador of Venice, did not

hesitate to take the field against the enemies of the Holy See and

more especially against Luther himself. In a work entitled Assertio

Septem Sacramentorum (Defense of the Seven Sacraments) published

against Luther in 1521, he defended in no uncertain terms the rights

and privileges of the Holy See, and in return for the very valuable

services that he rendered to religion he was honored by Leo X. with

the title Fidei Defensor (Defender of the Faith, 1521). The

example of the king, and the activity of Cardinal Wolsey and of the

bishops, made it impossible for the few individuals who favored the

German movement to spread their views.

Were it not for Henry's eagerness to secure a separation from his

wife, Catharine of Aragon, it is highly improbable that the anti-Roman

agitation would have made any considerable progress in England. In

1499 Henry's wife, Catharine of Aragon, had been betrothed by proxy to

his brother Prince Arthur, heir- pparent to the English throne. She

arrived in England two years later, and the marriage was solemnized at

St. Paul's on the 14th November, 1501. Prince Arthur was then only a

boy of fifteen years of age, and of so delicate a constitution that

fears were entertained by many that his wife must soon don the widow's

weeds. Unfortunately these fears were speedily justified. In April

1502 the Prince fell a victim to a pestilence that raged in the

district round Ludlow Castle to which he and his wife had retired. To

prevent quarrels between Ferdinand and Henry VII. regarding

Catharine's dowry, a marriage was arranged between Catharine and

Prince Henry. The necessary dispensation for a marriage with a

deceased brother's wife was granted by Julius II. (December 1503), and

according to the agreement between the courts of England and of Spain,

the marriage should have taken place as soon as Henry reached the age

of puberty; but owing to certain political changes in Spain, and the

prospect of securing a better match for the heir presumptive to the

English throne, Henry VII. arranged that Prince Henry should appear

before Fox, Bishop of Winchester, and lodge a formal protest against a

marriage agreement that had been concluded during his minority and

which he now declared to be null and void (17th June, 1505). This

protest was kept secret, but for years Catharine was treated with

neglect and left in doubt regarding her ultimate fate. As soon,

however, as Henry was free to act for himself on the death of his

father, the marriage between himself and Catharine was solemnized

publicly (1509), and on the 24th June of the same year the king and

queen were crowned at Westminster Abbey.

For years Henry and Catharine lived happily together as man and wife.

Several children were born to them, all of whom unfortunately died in

their infancy except the Princess Mary, afterwards Queen Mary of

England. Even before there was any question of separation from his

wife, Henry's relations with some of the ladies at court were not

above suspicion. By one, Elizabeth Blount, he had a son whom he

created Duke of Richmond and to whom at one time he thought of

bequeathing the crown of England. In a short time Mary, the eldest

sister of Anne Boleyn, succeeded to Elizabeth in the affections of the

king. The fact that Catharine was some years older than her husband,

that infirmity and sorrow for the death of her children had dimmed her

charms, and that there could be no longer any hope for the birth of an

heir to the throne, preyed on Henry's mind and made him not unwilling

to rid himself of a wife, whom, however, he could not but admire even

though she had forfeited his love. Were he to die there was no one to

succeed him but the Princess Mary, and her right to the throne might

be contested. Even though she succeeded, her marriage must inevitably

create great difficulties. Were she to marry a foreign prince, he

feared that England might become a province; were she to accept the

hand of an English nobleman, a disputed succession ending in civil war

was far from being improbable. His gloomy anticipations were shared in

by many of his advisers; and Wolsey, who had set his heart on uniting

the forces of England and France against the Emperor, was not

unwilling to set a seal on the new French anti-imperial alliance by

repudiating Henry's marriage with the Emperor's aunt, if such a

dissolution could be brought about without infringing the laws of God.

Though it would seem that doubts had long since arisen in Henry's mind

regarding the lawfulness of his marriage to his deceased brother's

wife, and that questions of policy may have influenced the attitude of

his advisers towards the projected separation, yet it is certain that

it was the charms of the young and accomplished Anne Boleyn, that

brought matters to a crisis. With her experience of the gay and

corrupt court of France, she was not likely to be mistaken about the

influence of her charms or the violence of the king's passion. She

would be the king's wife if he wished; but she would not be, like her

sister, the king's mistress. Overcome by the force of his desires, he

determined to rid himself of a wife of whom he was tired, in favor of

her young and more attractive rival. The fact that Catharine had been

married to his brother Arthur was seized upon by him to furnish a

decent pretext for the projected separation. His conscience, he

averred, reproached him for such an incestuous alliance, and for his

own peace of mind it was necessary, he maintained, to submit the

validity of his marriage to the decision of the Church.

There is no convincing evidence that the idea of a separation from

Catharine originated with Cardinal Wolsey, though the latter, longing

for a matrimonial alliance of his king with a French princess, and not

aware of Henry's intention with regard to Anne, was probably not sorry

when he learned of Henry's scruples; and it is not true to say that

the first doubts regarding the illegitimacy of the Princess Mary were

raised by the French Ambassador in 1527. The whole story of the

negotiations with France regarding Mary's marriage at the time, makes

it perfectly clear that her legitimacy was assumed. The divorce

proceedings originated in Henry's own mind, and the plan of marrying

Anne Boleyn was kept a secret from Wolsey and from most of the royal

advisers. When exactly the question of a separation from Catharine was

first mooted is uncertain; but there can be no doubt that early in

1527 active steps were taken to secure a condemnation of the marriage.

Wolsey entered warmly into the project, but most of the bishops whom

he consulted were not anxious to assist him; and what was still more

serious Fisher, the learned and saintly Bishop of Rochester, declared

himself from the beginning a determined opponent. The capture of Rome

by imperial troops (1527) made it imperative that the terms of the

French alliance should be completed at once, and Cardinal Wolsey set

out for Paris as the representative of England. While Wolsey was

absent in France arranging the terms of the alliance, Anne Boleyn took

occasion to warn Henry that his great minister was unreliable, that in

his heart he was opposed to the separation, and that without his

knowledge or consent negotiations should be opened directly with the

Roman court. An agent was dispatched to Rome and succeeded in securing

an interview with Clement VII., after the latter had made his escape

from Rome to Orvieto (December 1527). It was contended on behalf of

the king that the dispensation granted by Julius II. was null and

void. In proof of this it was contended: that in the Bull it had been

stated that Henry desired to marry Catharine, and that the marriage

was necessary for preserving peace between England and Spain, both of

which statements, it was alleged, were false; that at the time the

disposition was granted Henry was only twelve years of age and

therefore incapable of accepting it; that several persons mentioned in

the Bull, as for example, Queen Isabella and Henry VII., had died

before the marriage took place; and lastly that when Henry reached the

age of puberty he had protested against the marriage, thereby

renouncing for himself the favors granted in the Bull of

dispensation. Later on it was contended, by those who favored the

separation, that the dispensation was issued by the Pope on the

supposition that the marriage between Arthur and Catharine had not

been consummated, and that therefore, since this condition was not

verified, the dispensation was invalid. But here they were faced with

the difficulty that the great weight of evidence favored the view

that the marriage had not been consummated; that in any case the

dispensation was ample enough to cover both the impediment of affinity

and public honesty; and that, whatever might be said against the Bull

of dispensation, no such objection could be urged against the brief

said to have been forwarded by the Pope to the court of Spain. As

the English agents had been instructed to seek not merely the

appointment of a commission to declare the invalidity of the

dispensation, and consequently of the marriage, but also for a

dispensation which would permit the king to marry a woman related to

him in the first degree of affinity, whether the affinity had been

contracted by a lawful or unlawful connection, it was thought prudent

not to lay stress on the argument that marriage with the deceased

brother's wife was prohibited by the divine law, and that, therefore,

the Pope could not grant a dispensation such as had been issued by

Julius II. At a later date great stress was laid upon this argument.

Clement VII., while not unwilling to grant the dispensation

requested, did not think it consistent with his own honor or that

of the king, to grant the commission according to the terms drawn up

for him in England. A new embassy, consisting of Edward Foxe, and Dr.

Stephen Gardiner, Wolsey's secretary, was dispatched, and arrived at

Orvieto in March 1528. The victorious progress of the French armies in

Italy (1527-28), by relieving Clement VII. from the pressure of the

imperial party, favored the petition of Henry VIII. Arguments drawn

from canon law and from theology were driven home by Gardiner with a

fluency and wealth of knowledge that astonished the papal advisers,

and when arguments failed, recourse was had to threats of an appeal to

a general council, and of the complete separation of England from the

Holy See. The decretal commission demanded by the English ambassadors

was, however, refused; but, in its place, a decree was issued

empowering Cardinal Wolsey and Cardinal Campeggio to try the case in

England and to pronounce a verdict in accordance with the evidence

submitted to them. As this fell very far short of what had been

demanded by the English envoys, new demands were made for a more ample

authority for the commission, and in view of the danger that

threatened the Catholic Church in England, Clement VII. yielded so far

as to promise that he would not revoke the jurisdiction of those whom

he had entrusted with the trial of the case (July 1528).

Meanwhile news of what was in contemplation was noised abroad. Many of

the English merchants, fearing that hostility to the empire would lead

to an interruption of their trade especially with the Netherlands,

detested the new foreign policy of the king, while the great body of

the people were so strongly on the side of Catharine that were a

verdict to be given against her a popular rebellion seemed inevitable.

So pronounced was this feeling even in the city of London itself, that

Henry felt it necessary to summon the Lord Mayor and the Corporation

to the royal palace, where he addressed them on the question that was

then uppermost in men's minds. He spoke of Catharine in terms of the

highest praise, assured them that the separation proceedings were

begun, not because he was anxious to rid himself of a wife whom he

still loved, but because his conscience was troubled with scruples

regarding the validity of his marriage, and that the safety of the

kingdom was endangered by doubts which had been raised by the French

ambassador regarding the legitimacy of Princess Mary. To put an end to

these doubts, and to save the country from the horror of a disputed

succession, the Pope had appointed a commission to examine the

validity of the marriage; and to the judgment of that commission

whatever it might be he was prepared to yield a ready submission. He

warned his hearers, however, that if any person failed to speak of him

otherwise than became a loyal subject towards his sovereign condign

punishment would await him. To give effect to these words a search was

made for arms in the city, and strangers were commanded to depart from

London.

Though the commission had been granted in April, Cardinal Campeggio

was in no hurry to undertake the work that was assigned to him. He did

not leave Rome till June, and he proceeded so leisurely on his journey

through France that it was only in the first week of October that he

arrived in London. In accordance with his instructions, he endeavored

to dissuade the king from proceeding further with the separation, but

as Henry was determined to marry the lady of his choice even though it

should prove the ruin of his kingdom, all the efforts of Campeggio in

this direction were in vain. He next turned his attention to

Catharine, in the hope of persuading her to enter a convent, only to

discover that her refusal to take any step likely to cast doubts upon

her own marriage and the legitimacy of her daughter was fixed and

unalterable. At the queen's demand counsel was assigned to her to

plead her cause. The situation was complicated by the fact that Julius

II. appears to have issued two dispensations for Henry's marriage, one

contained in the Bull sent to England, the other in a brief forwarded

to Ferdinand in Spain. The queen produced a copy of the brief, which

was drawn up in such a way as to elude most of the objections that

were urged against the Bull on the ground that the marriage had been

consummated. The original of the brief was in the hands of the

Emperor, and various attempts were made to secure the original or to

have it pronounced a forgery by the Pope; but the Emperor was too wily

a diplomatist to be caught so easily, and the Pope refused either to

order its production or to condemn it without evidence as a

forgery. This question of the brief was seized upon by Cardinal

Campeggio as a good opportunity for delaying the trial. At last on the

31st May 1529, the legates Wolsey and Campeggio opened the court at

Blackfriars, and summoned Henry and Catharine to appear before them in

person or by proxy on the 18th June. Both king and queen answered the

summons, the latter, however, merely to demand justice publicly from

the king, to protest against the competence and impartiality of the

tribunal, and to lodge a formal appeal to Rome. Her appeal was

disallowed, and on her refusal to take any further part in the trial

she was condemned as contumacious; but even still she was not without

brave and able defenders. Bishop Fisher of Rochester spoke out

manfully against the unnatural and unlawful proceedings, and his

protest found an echo not merely in the court itself but throughout

the country. The friends of Henry, fearing that the Pope might revoke

the power of the legates, clamored for an immediate verdict; but this

Campeggio was determined to prevent at all costs. By insisting upon

all the formalities of law he took care to delay the proceedings till

the 23rd July, when he announced that the legatine court should follow

the rules of the Roman court, and should, therefore, adjourn to

October. Already he was aware of the fact that Clement VII., yielding

to the entreaties of Catharine and the demands of the Emperor, had

reserved the decision of the case to Rome (19th July), and that the

summons to the king and queen to proceed there to plead their cause

was already on its way to England.

Henry, disguising his real feelings, pretended to be satisfied; but in

reality his disappointment was extreme. Anne Boleyn and her friends

threw the blame entirely on Wolsey. They suggested that the cardinal

had acted a double part throughout the entire proceedings. For a time

there was a conflict in the king's mind between the suggestions of his

friends and the memory of Wolsey's years of loyal service; but at last

Henry was won over to the party of Anne, and Wolsey was doomed to

destruction. He was deprived of the office of Lord Chancellor which

was entrusted to Sir Thomas More (Oct. 1529), accused of violating the

statute of Praemunire by exercising legatine powers, a charge to which

he pleaded guilty though he might have alleged in his defense the

permission and authority of the king, indicted before Parliament as

guilty of high treason, from the penalty of which he was saved by the

spirited defense of his able follower Thomas Cromwell (Dec.), and

ordered to withdraw to his diocese of York (1530). His conduct in

these trying times soon won the admiration of both friends and foes.

The deep piety and religion of the man, however much they might have

been concealed by his fondness for pomp and display during the days of

his glory, helped him to withstand manfully the onslaughts of his

opponents. His time was spent in prayer and in the faithful discharge

of his episcopal duties, but the enemies who had secured his downfall

at court were not satisfied. They knew that he had still a strong hold

on the affections of the king, and they feared that were any foreign

complications to ensue he might be recalled to court and restored to

his former dignities. They determined therefore to bring about his

death. An order for his arrest and committal to the Tower was issued,

but death intervened and saved him from the fate that was in store for

him. Before reaching London he took suddenly ill, and died after

having received the last consolations of religion (Nov. 1530).

Henry, having failed to obtain a favorable verdict from the legatine

commission, determined to frighten the Pope into compliance with his

wishes by showing him that behind the King of England stood the

English Parliament. The most elaborate precautions were taken to

secure that members likely to be friendly were elected. In many cases

together with the writs the names of those whose return the court

desired were forwarded to the sheriffs. The Parliament that was

destined to play such a momentous part in English affairs met in 1529.

It was opened by the king in person attended by Sir Thomas More as

Lord Chancellor. At a hint from the proper quarter it directed its

attention immediately to the alleged abuses of the clergy. The

principal complaints put forward were the excessive fees and delays in

connection with the probate of wills, plurality of benefices, and the

agricultural and commercial activity of priests, bishops, and

religious houses, an activity that was detrimental to themselves and

unfair to their lay competitors. Measures were taken in the House of

Commons to put an end to these exactions and abuses, but when the

bills reached the House of Lords Bishop Fisher lodged an emphatic

protest for which he was called to account by the king. When

Parliament had done enough to show the bishops and the Roman court

what might be expected in case Henry's wishes were not complied with

it was prorogued (Dec. 1529), and in the following month a solemn

embassy headed by the Earl of Wiltshire, Anne Boleyn's father, was

dispatched to interview the Pope and Charles V. at Bologna. The envoys

were instructed to endeavor to win over the Emperor to the king's

plans, but Charles V. regarded their advances with indignation and

refused to sacrifice the honor of his aunt to the friendship of

England. The only result of the embassy was that a formal citation of

Henry to appear at Rome was served on the Earl of Wiltshire, but at

the request of the latter a delay of some weeks was granted. Unless

some serious measures were taken immediately, Henry had every reason

to expect that judgment might be given against him at Rome, and that

he would find himself obliged either to submit unconditionally or to

defend himself against the combined forces of the Emperor and the King

of France.

To prevent or at least to delay such a result and to strengthen the

hands of the English agents at Rome, he determined to follow the

advice that had been given him by Thomas Cranmer, namely, to obtain

for the separation from Catharine the approval of the universities and

learned canonists of the world. Agents were dispatched to Cambridge

and Oxford to obtain a verdict in favor of the king. Finding it

impossible to secure a favorable verdict from the universities, the

agents succeeded in having the case submitted to a small committee

both in Cambridge and Oxford, and the judgment of the committees,

though by no means unanimous, was registered as the judgment of the

universities. Francis I. of France, who for political reasons was

on Henry's side throughout the whole proceedings, brought pressure to

bear upon the French universities, many of which declared that Henry's

marriage to Catharine was null and void. In Italy the number of

opinions obtained in favor of the king's desires depended entirely

upon the amount of money at the disposal of his agents. To support

the verdict of the learned world Henry determined to show Rome that

the nobility and clergy of his kingdom were in complete sympathy with

his action. A petition signed by a large number of laymen and a few of

the bishops and abbots was forwarded to Clement VII. (13th July,

1530). It declared that the question of separation, involving as

it did the freedom of the king to marry, was of supreme importance for

the welfare of the English nation, that the learned world had

pronounced already in the king's favor, and that if the Pope did not

comply with this request England might be driven to adopt other means

of securing redress even though it should be necessary to summon a

General Council. To this Clement VII. sent a dignified reply (Sept.),

in which he pointed out that throughout the whole proceedings he had

shown the greatest regard for Henry, and that any delay that had

occurred at arriving at a verdict was due to the fact that the king

had appointed no legal representatives at the Roman courts. The

French ambassador also took energetic measures to support the English

agents threatening that his master might be forced to join hands with

Henry if necessary; but even this threat was without result, and the

king's agents were obliged to report that his case at Rome was

practically hopeless, and that at any moment the Pope might insist in

proceeding with the trial.

When Henry realized that marriage with Anne Boleyn meant defiance of

Rome he was inclined to hesitate. Both from the point of view of

religion and of public policy separation from the Holy See was

decidedly objectionable. While he was in this frame of mind, a prey to

passion and anxiety, it was suggested to him, probably by Thomas

Cromwell, the former disciple of the fallen cardinal, that he should

seize this opportunity to strengthen the royal power in England by

challenging the authority of the Pope, and by taking into his own

hands the control of the wealth and patronage of the Church. The

prospect thus held out to him was so enticing that Henry determined to

follow the advice, not indeed as yet with the intention of involving

his kingdom in open schism, but in the hope that the Pope might be

forced to yield to his demands. In December 1530 he addressed a strong

letter to Clement VII. He demanded once more that the validity of his

marriage should be submitted to an English tribunal, and warned the

Pope to abstain from interfering with the rights of the king, if he

wished that the prerogatives of the Holy See should be respected in

England.

This letter of Henry VIII. was clearly an ultimatum, non-compliance

with which meant open war. At the beginning of 1531 steps were taken

to prepare the way for royal supremacy. For exercising legatine powers

in England Cardinal Wolsey had been indicted and found guilty of the

violation of the stature of Praemunire, and as the clergy had

submitted to his legatine authority they were charged as a body with

being participators in his guilt. The attorney-general filed an

information against them to the court of King's Bench, but when

Convocation met it was intimated to the clergy that they might procure

pardon for the offence by granting a large contribution to the royal

treasury and by due submission to the king. The Convocation of

Canterbury offered a sum of £100,000, but the offer was refused unless

the clergy were prepared to recognize the king as the sole protector

and supreme head of the church and clergy in England. To such a novel

proposal Convocation showed itself decidedly hostile, but at last

after many consultations had been held Warham, the aged Archbishop of

Canterbury, proposed that they should acknowledge the king as "their

singular protector only, and supreme lord, and as far as the law of

Christ allows even supreme head." "Whoever is silent," said the

archbishop, "may be taken to consent," and in this way by the silence

of the assembly the new formula was passed. At the Convocation of

York, Bishop Tunstall of Durham, while agreeing to a money payment,

made a spirited protest against the new title, to which protest Henry

found it necessary to forward a reassuring reply. Parliament then

ratified the pardon for which the clergy had paid so dearly, and to

set at rest the fears of the laity a free pardon was issued to all

those who had been involved in the guilt of the papal legate.

Clement VII. issued a brief in January 1531, forbidding Henry to marry

again and warning the universities and the law courts against giving a

decision in a case that had been reserved for the decision of the Holy

See. When the case was opened at the Rota in the same month an

excusator appeared to plead, but as he had no formal authority from

the king he was not admitted. The case, however, was postponed from

time to time in the hope that Henry might relent. In the meantime at

the king's suggestion several deputations waited upon Catharine to

induce her to recall her appeal to Rome. Annoyed by her obstinacy

Henry sent her away from court, and separated from her her daughter.

After November 1531, the king and queen never met again. Popular

feeling in London and throughout England was running high against the

divorce, and against any breach with the Emperor, who might close the

Flemish markets to the English merchants. The clergy, who were

indignant that their representatives should have paid such an immense

sum to secure pardon for an offence of which they had not been more

guilty than the king himself, remonstrated warmly against the taxation

that had been levied on their revenues. Unmindful of the popular

commotion, Henry proceeded to usurp the power of the Pope and of the

bishops, and though he was outwardly stern in the repression of

heresy, the friends of the Lutheran movement in England boasted

publicly that the king was on their side.

When Parliament met again (Jan. 1532), the attacks on the clergy were

renewed. A petition against the bishops, drawn up by Thomas Cromwell

at the suggestion of Henry, was presented in the name of the House

of Commons to the king. In this petition the members were made to

complain that the clergy enacted laws and statutes in Convocation

without consulting the king or the Commons, that suitors were treated

harshly before the ecclesiastical courts, that in regard to probates

the people were worried by excessive fees and unnecessary delays, and

that the number of holidays was injurious to trade and agriculture.

This complaint was forwarded to Convocation for a reply. The bishops,

while vindicating for the clergy the right to make their own laws and

statutes, showed themselves not unwilling to accept a compromise, but

Parliament at the instigation of Henry refused to accept their

proposals. The king, who was determined to crush the power of the

clergy, insisted that Convocation should abandon its right to make

constitutions or ordinances without royal permission, and that the

ordinances passed already should be submitted to a mixed commission

appointed by the authority of the crown. Such proposals, so contrary

to the customs of the realm and so destructive of the independence of

the Church, could not fail to be extremely disagreeable to the

bishops; but in face of the uncompromising attitude of the king they

were forced to give way, and in a document known as the Submission of

the Clergy they sacrificed the legislative rights of Convocation (May

1532). They agreed to enact no new canons, constitutions or ordinances

without the king's consent, that those already passed should be

submitted to a committee consisting of clergy and laymen nominated by

the king, and that the laws adopted by this committee and approved by

the king should continue in full force. Sir Thomas More, who had

worked hard in defense of the Church, promptly resigned his office of

Lord Chancellor that he might have a freer hand in the crisis that had

arisen.

In March 1532 another step was taken to overawe the Roman court and

force the Pope to yield to Henry's demands. An Act was passed

abolishing the Annats or First Fruits paid to Rome by all bishops on

their appointment to vacant Sees. If the Pope should refuse to appoint

without such payments, it was enacted that the consecration should be

carried out by the archbishop of the province without further recourse

to Rome. Such a measure, tending so directly towards schism, met with

strong opposition in the House of Lords from the bishops, abbots, and

many of the lay lords, as it did also in the House of Commons. In the

end, it was passed only on the understanding that it should not take

effect for a year, and that in the meantime if an agreement could be

arrived at with the Pope, the king might by letters patent repeal it.

Henry instructed his ambassador at Rome to inform Clement VII. that

this legislation against Annats was entirely the work of the

Parliament, and that if the Pope wished for its withdrawal he must

show a more conciliatory spirit towards the king and people of

England.

The Pope, however, refused to yield to such intimidation. When news

arrived at Rome that Henry had sent away Catharine from court, the

question of excommunication was considered, but as the excommunication

of a king was likely to be fraught with such serious consequences for

the English Church, Clement VII. hesitated to publish it in the hope

that Henry might see the error of his ways. The trial was delayed from

time to time until at last in November 1532 the Pope addressed a

strong letter to the king, warning him under threat of excommunication

to put away Anne Boleyn, and not to attempt to divorce Catharine or to

marry another until a decision had been given in Rome. By this

time the king had given up all hope of securing the approval of Rome

for the step he contemplated. Even in England the divorce from

Catharine found much opposition from both clergy and laity. Sir Thomas

More and many of the nobles were on the side of Catharine, as were

also Bishop Fisher of Rochester and Bishop Tunstall of Durham. Even

Reginald Pole, the king's own cousin, who had been educated at Henry's

expense, and for whom the Archbishopric of York had been kept vacant,

refused the tempting offers that were made to him on condition that he

would espouse the cause of separation. He preferred instead to leave

England rather than act against his conscience by supporting

Catherine's divorce. Fortunately for Henry at this moment Warham,

the aged Archbishop of Canterbury, who was a stout defender of the

Holy See, passed away (Aug. 1532). The king determined to secure

the appointment of an archbishop upon whom he could rely for the

accomplishment of his designs, and accordingly Thomas Cranmer was

selected and presented to Rome. After much hesitation, and merely as

the lesser of two evils, his appointment was confirmed.

Thomas Cranmer was born in Nottingham, and educated in Cambridge. He

married early in life, but his wife having died within a few months,

he determined to take holy orders. His suggestion to submit the

validity of Henry's marriage to the judgment of the universities,

coming as it did at a time when Henry was at his wits' end, showed him

to be a man of resource whose services should be secured by the court.

He was appointed accordingly chaplain to Anne Boleyn's father, and was

one of those sent on the embassy to meet the Pope and Charles V. at

Bologna. During his wanderings in Germany he was brought into close

relationship with many of the leading Reformers, and following their

teaching and example he took to himself a wife in the person of the

well-known Lutheran divine, Osiander. Such a step, so highly

objectionable to the Church authorities and likely to be displeasing

to Henry, who in spite of his own weakness insisted on clerical

celibacy, was kept a secret, though it is not at all improbable that

the secret had reached the ears of the king. At the time when the

latter had made up his mind to set Rome at defiance, he knew how

important it was for him to sacrifice his own personal predilections,

for the sake of having a man of Cranmer's pliability as Archbishop of

Canterbury, and head of the clergy in England. On the 30th March,

1533, Cranmer was consecrated archbishop, and took the usual oath of

obedience and loyalty to the Pope; but immediately before the

ceremony, he registered a formal protest that he considered the oath a

mere form, and that he wished to hold himself free to provide for the

reformation of the Church in England. Such a step indicates

clearly enough the character of the first archbishop of the

Reformation in England.

To prepare the way for the sentence that might be published at any

moment by the Pope a bill was introduced forbidding appeals to Rome

under penalty of Praemunire, and declaring that all matrimonial suits

should be decided in England, and that the clergy should continue

their ministrations in spite of any censures or interdicts that might

be promulgated by the Pope. The bill was accepted by the House of

Lords, but met with serious opposition in the Commons. An offer was

made to raise £200,000 for the king's use if only he would refer the

whole question to a General Council, but in the end, partly by threats

and partly by deception regarding the attitude of the Pope and the

Emperor, the opposition was induced to give way and the bill became

law. By this Act it was declared that the realm of England should be

governed by one supreme head and king, to whom both spirituality and

temporality were bound to yield, "next to God a natural and humble

obedience," that the English Church was competent to manage its own

affairs without the interference of foreigners, and that all spiritual

cases should be heard and determined by the king's jurisdiction and

authority. The question of the divorce was brought before the

Convocation in March 1533, and though Fisher spoke out boldly in

defense of Catharine's marriage, his brethren failed to support him,

and Convocation declared against the legitimacy of the marriage.

Henry was now free to throw off the mask. He could point to the

verdict given in his favor by both Parliament and Convocation, and

could rely on Cranmer as Archbishop of Canterbury to carry out his

wishes. In order to provide for the legitimacy of the child that was

soon to be born, he had married Anne Boleyn privately in January 1533.

In April Cranmer requested permission to be allowed to hold a court to

consider Henry's marriage with Catharine, to which request, inspired

as it had been by himself, the king graciously assented. The court sat

at Dunstable, where Catharine was cited to appear. On her refusal to

plead she was condemned as contumacious. Sentence was given by the

archbishop that her marriage with Henry was invalid (23rd April,

1533). Cranmer next turned his attention to Henry's marriage with

Anne, and as might be expected, this pliant minister had no difficulty

in pronouncing in its favor. On Whit Sunday (1533) Anne was crowned

as queen in Westminster Abbey. The popular feeling in London and

throughout the kingdom was decidedly hostile to the new queen and to

the French ambassador, who was blamed for taking sides against

Catharine, but Henry was so confident of his own power that he was

unmoved by the conduct of the London mob. In September, to the great

disappointment of the king who had been led by the astrologers and

sorcerers to believe that he might expect the advent of an heir, a

daughter was born to whom was given the name Elizabeth.

The Pope, acting on the request of the French and English ambassadors,

had delayed to pronounce a definitive sentence, but the news of

Henry's marriage with Anne and of the verdict that had been

promulgated by the Archbishop of Canterbury made it imperative that

decisive measures should be taken. On the 11th July it was decreed

that Henry's divorce from Catharine and his marriage with Anne were

null and void. Sentence of excommunication against him was

prepared, but its publication was postponed till September, when an

interview had been arranged to take place between the Pope and Francis

I. Francis I. was not without hope even still that an amicable

settlement could be arranged. Throughout the whole proceedings he had

espoused warmly Henry's cause, in the belief that England, having

broken completely with Catharine's nephew Charles V., might be forced

to conclude an alliance with France; but he never wished that Henry

VIII. should set the Holy See at defiance, or that England should be

separated from the Catholic Church. To the Pope and to Henry he had

addressed his remonstrances and petitions in turn, but events had

reached such a climax that mediation was almost an impossibility. The

interview arranged between the Pope and Francis I. took place at

Marseilles in October 1533. Regardless of all the rules of diplomatic

courtesy and of good manners, Henry's representative forced his way

into the presence of the Pope, and announced to him that the King of

England had appealed from the verdict of Rome to the judgment of a

General Council. Notices of this appeal were posted up in London, and

preachers were ordered to declaim against the authority of the Pope,

who was to be styled henceforth Bishop of Rome, and whose sentences

and excommunications, the people were to be informed, were of no

greater importance than those of any other foreign bishop. The way was

now open for the final act of separation.

Parliament met in January 1534. The law passed the previous year

against the payment of annats was now promulgated. According to this

Act the Pope was not to be consulted for the future regarding

appointments to English Sees. When a bishopric became vacant, the

chapter having received the Congé d'élire should proceed to elect

the person named in the royal letters accompanying the Congé, and

the person so elected should be presented to the metropolitan for

consecration. In case of a metropolitan See, the archbishop-elect

should be consecrated by another metropolitan and two bishops or by

four bishops appointed by the crown. Another Act was passed forbidding

the payment of Peter's Pence and all other fees and pensions paid

formerly to Rome. The Archbishop of Canterbury was empowered to grant

dispensations, and the penalties of Praemunire were leveled against

all persons who should apply for faculties to the Pope. By a third Act

a prohibition against appeals to Rome was renewed, although it was

permitted to appeal from the court of the Archbishop of Canterbury to

the king's Court of Chancery. Convocation was forbidden to enact any

new ordinances without the consent of the king, and those passed

already were to be subject to revision by a royal commission. Finally,

an Act was passed vesting the succession in the children of Henry and

Anne to the exclusion of the Princess Mary. The marriage with

Catharine was declared null and void by Parliament on the ground

principally that no man could dispense with God's law, and to prevent

such incestuous unions in the future a list of the forbidden degrees

was drawn up, and ordered to be exhibited in the public churches. To

question the marriage of Henry with Anne Boleyn by writing, word,

deed, or act was declared to be high treason, and all persons should

take an oath acknowledging the succession under pain of misprision of

treason. That the Parliament was forced to adopt these measures

against its own better judgment is clear from the small number of

members who took their seats in the House of Lords, as well as from

the fact that some of the Commoners assured the imperial ambassador

that were his master to invade England he might count on considerable

support.

In Rome the agents of Francis I., fearing that an alliance between

France and England would be impossible were Henry to throw off his

allegiance to the Church, moved heaven and earth to prevent a

definitive sentence. The fact that the Emperor was both unable and

unwilling to enforce the decision of the Pope, and that instead of

desiring the excommunication and deposition of Henry he was opposed to

such a step, made it more difficult for the Pope to take decisive

measures. Finally after various consultations with the cardinals,

sentence was given declaring the marriage with Catharine valid and the

children born of that marriage legitimate (23rd March, 1534). When the

news of this decision reached England Henry was alarmed. He feared

that the Emperor might declare war at any moment, that an imperial

army might be landed on the English shores, and that Francis I.

yielding to the entreaties of the Pope might make common cause with

the imperialists. Orders were given to strengthen the fortifications,

and to hold the fleet in readiness. Agents were dispatched to secure

the neutrality of France, and preachers were commanded to denounce the

Bishop of Rome. As matters stood, however, there was no need for such

alarm. The Emperor had enough to engage his attention in Spain and

Germany, and the enmity between Charles V. and the King of France was

too acute to prevent them from acting together even in defense of

their common religion.

Meantime it was clear to Henry that popular feeling was strong against

his policy, but instead of being deterred by this, he became more

obstinate and determined to show the people that his wishes must be

obeyed. A nun named Elizabeth Barton, generally known as the "Nun of

Kent," claimed to have been favored with special visions from on

high. She denounced the king's marriage with Anne, and bewailed the

spread of heresy in the kingdom. People flocked from all parts to

interview her, and even Cranmer pretended to be impressed by her

statements. She and many of her principal supporters were arrested and

condemned to death (Nov. 1534). It was hoped that by her confession it

might be possible to placate Bishop Fisher, who was specially hated by

Henry on account of the stand he had made on the question of the

marriage, and the late Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More. Both had met

the nun, but had been careful to avoid everything that could be

construed even remotely as treason. In the Act of Attainder introduced

into Parliament against Elizabeth Barton and her confederates, the

names of Fisher and More were included, but so strong was the feeling

in More's favor that his name was erased. Fisher, although able to

clear himself from all reasonable grounds of suspicion, was found

guilty of misprision of treason and condemned to pay a fine of £300.

Fisher and More were then called upon to take the oath of succession,

which, as drawn up, included, together with an acknowledgement of the

legitimacy of the children born of Henry and Anne, a repudiation of

the primacy of the Pope, and of the validity of Henry's marriage with

Catharine. Both were willing to accept the succession as fixed by Act

of Parliament, but neither of them could accept the other

propositions. They were arrested therefore and lodged in the Tower

(April 1534).

Commissions were appointed to minister the oath to the clergy and

laity, most of whom accepted it, some through fear of the consequences

of refusal and others in the hope of receiving a share of the monastic

lands, which, it was rumored, would soon be at the disposal of the

king. A royal commission consisting of George Brown, Prior of the

Augustinian Hermits, and Dr. Hilsey, Provincial of the Dominicans, was

appointed to visit the religious houses and to obtain the submission

of the members (April 1534). By threats of dissolution and

confiscation they secured the submission of most of the monastic

establishments with the exception of the Observants of Richmond and

Greenwich and the Carthusians of the Charterhouse, London. Many of the

members of these communities were arrested and lodged in the Tower,

and the decree went forth that the seven houses belonging to the

Observants, who had offered a strenuous opposition to the divorce,

should be suppressed. The Convocations of Canterbury and York

submitted, as did also the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

When Parliament met again in November 1534 a bill was introduced

proclaiming the king supreme head of the Church in England. The

measure was based upon the recognition of royal supremacy extracted

from Convocation three years before, but with the omission of the

saving clause "as far as the law of Christ allows." According to this

Act it was declared that the king "justly and rightly is and ought to

be the supreme head of the Church in England, and to enjoy all the

honors, dignities, pre-eminences, jurisdictions, privileges,

authorities, immunities, profits and commodities" appertaining to the

dignity of the supreme head of the Church. An Act of Attainder was

passed against Fisher, More, and all others who had refused

submission. The First Fruits, formerly paid to the Pope, were to be

paid to the king, and bishops were allowed to appoint men approved by

the crown to be their assistants.

By these measures the constitution of the Church, as it had been

accepted for centuries by the English clergy and laity, was

overturned. The authority of the Pope was rejected in favor of the

authority of the king, who was to be regarded in the future as the

source of all ecclesiastical jurisdiction. This great religious

revolution was carried out without the consent of the bishops and

clergy. With the single exception of Cranmer the bishops to a man

opposed the change, and if they and the great body of the clergy made

their submission in the end, they did so not because they were

convinced by the royal arguments, but because they feared the royal

displeasure. Neither was the change favored by any considerable

section of the nobles and people. The former were won over partly by

fear, partly by hope of securing a share in the plunder of the Church;

the latter, dismayed by the cowardly attitude shown by their spiritual

and lay leaders, saw no hope of successful resistance. Had there been

any strong feeling in England against the Holy See, some of the

bishops and clergy would have spoken out clearly against the Pope, at

a time when such a step would have merited the approval of the king.

The fact that the measure could have been passed in such circumstances

is in itself the best example of what is meant by Tudor despotism, in

the days when an English Parliament was only a machine for registering

the wishes of the king.

In January 1535 an order was made that the king should be styled

supreme head of the Church of England. Thomas Cromwell, who had risen

rapidly at court in spite of the disgrace of his patron, Cardinal

Wolsey, was entrusted with the work of forcing the clergy and laity to

renounce the authority of the Pope. The bishops were commanded to

surrender the Bulls of appointment they had received from Rome, and to

acknowledge expressly that they recognized the royal supremacy.

Cromwell was appointed the king's vicar-general, from whom the bishops

and archbishops were obliged to take their directions. Severe measures

were to be used against anybody who spoke even in private in favor of

Rome. The Prior of the London Charterhouse and some other Carthusians

were brought to trial for refusing to accept the royal supremacy

(April, 1535). After an able and uncompromising defense they were

found guilty of treason and were put to death with the most revolting

cruelty. Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More, who were prisoners in

the Tower, were allowed some time to consider their course of conduct.

Fisher declared that he could not acknowledge the king as supreme head

of the Church. While he lay in prison awaiting his trial, Paul III.,

in acknowledgment of his loyal services to the Church, conferred on

him a cardinal's hat. This honor, however well merited, served only

to arouse the ire of the king. He declared that by the time the hat

should arrive Fisher should have no head on which to wear it, and to

show that this was no idle threat a peremptory order was dispatched

that unless Fisher and More took the oath before the feast of St. John

they should suffer the penalty prescribed for traitors. Fisher,

together with some monks of the Carthusians, was brought to trial

(June 1535), and was found guilty of treason for having declared that

the king was not supreme head of the Church. The prisoners were

condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. In the case of the

Carthusians the sentence was carried out to the letter, but as it was

feared that Fisher might die before he reached Tyburn he was beheaded

in the Tower (22nd June), and his head was impaled on London

bridge.

Sir Thomas More was placed on his trial in Westminster Hall before a

special commission (1st July). Able lawyer as he was, he had no

difficulty in showing that by silence he had committed no crime and

broken no Act of Parliament, but no defense could avail him against

the wishes of the king. The jury promptly returned a verdict of

guilty. Before sentence was passed the prisoner spoke out manfully

against royal supremacy, and in defense of the authority of Rome. He

declared that the Act of Parliament, which conferred on the king the

title of supreme head of the Church, was opposed both to the laws of

God and man, that it was in flagrant contradiction to the Magna

Charta, and that the king of England could no more refuse obedience to

the Holy See than a child could refuse obedience to his father. Even

after his trial and condemnation another attempt was made to induce

him to submit, but he refused, and on the 6th July he finished his

career as a martyr for Rome.

The execution of Fisher and More showed plainly to all that the breach

with Rome was not likely to be healed. When news of what had taken

place in England reached Rome Paul III. was anxious to issue a decree

of deposition against Henry. Had he done so, and had he been supported

by the Emperor and Francis I. there is no doubt that many of the

English noblemen would have joined the standard of the invaders, but

the hostility between France and the Emperor saved Henry. Neither

party was willing to aid the Pope lest the other should form an

alliance with England. Fearing such a union, however, between Francis

I. and Charles V. Henry hastened to seek the aid of the Protestant

princes of Germany. From 1531 he had been in communication with them

urging them to be careful about introducing religious innovations, but

he was now so alarmed lest the Emperor and the King of France might

join hands to assist the Pope in convoking a General Council, that

English envoys were directed to meet the Protestant princes at

Schmalkald (1535), to arrange for common action. A close union between

England and the Protestant states of Germany could not be effected,

because the Protestant princes insisted that Henry should accept the

Confession of Augsburg, and Henry refused to permit such interference

in the religious affairs of England. Still, English divines were

instructed to remain at Wittenberg, and Lutheran theologians were

invited to come to England for the discussion of religious

differences.

Meanwhile Cromwell was engaged in a visitation of the monasteries of

England (1535). To bring home to the minds of the bishops the meaning

of royal supremacy, he suspended their visitations while the royal

visitors were at work. Cromwell, unable to undertake the duty himself,

appointed delegates, and supplied them with the list of questions that

should be administered. His principal delegates were Richard Leyton

and Thomas Leigh, both men, as is evident from their own letters, who

were not likely to be over scrupulous about the methods they employed.

They were harsh, rude, and brutal in their treatment of both monks and

nuns, especially in houses where they suspected hostility to the

recent laws. They used every means in their power to break up the

harmony of religious life, and to unsettle the minds of the younger

members of the communities. In a few months the visitations were

finished, and the reports of the visitors were presented to Cromwell.

According to these reports most of the monasteries and convents were

homes of sin and vice, and many of the monks and nuns were guilty of

heinous crimes, but, though in particular instances there may have

been some grounds for these charges, there is good reason for not

accepting as trustworthy this account of monastic discipline. In the

first place the royal visitors traversed the country with such

lightning-like rapidity that it would have been impossible for them to

arrive at a correct judgment even had they been impartial and honest

men. That they were neither honest nor impartial is clear enough from

their own correspondence. They were sent out by Cromwell to collect

evidence that might furnish a decent pretext for suppressing the

monasteries and for confiscating the monastic possessions, and they

took pains to show their master that his confidence in them had not

been misplaced. Their only mistake was that in their eagerness to

black the character of the unfortunate religious they exceeded the

limits of human credulity. They positively reveled in sin, and the

scandals they reported were of such a gross and hideous kind that it

is impossible to believe that they could have been true, else the

people, instead of taking up arms to defend the religious houses,

would have risen in revolt to suppress such abominations. Nor is it

correct to say that the Comperta were submitted to Parliament for

discussion, and that the members were so shocked by the tale they

unfolded that they clamored for the suppression of these iniquitous

institutions. There is abundant evidence to prove that Parliament was

reluctant to take any action against the religious houses, that it was

only by the personal intervention of the king that the bill for the

suppression of the lesser monasteries was allowed to pass, and that it

is at least doubtful if any but general statements founded on the

Comperta were brought before Parliament. The story of the production

of the "Black Book" supposed to contain the reports is of a much later

date, and comes from sources that could not be regarded as

unprejudiced. It had its origin probably in a misunderstanding of the

nature of the Compendium Compertorum, which dealt only with parishes

of the northern province. It is strange that though the commissioners

made no distinction between the condition of the larger and the

smaller monasteries, the Act of Parliament based upon these reports

decreed only the suppression of the smaller monasteries, as if vice

and neglect of discipline were more likely to reign in the small

rather than in the larger communities; and it is equally strange that

the superiors of many of the houses, about which unfavorable reports

had been presented, were promoted to high ecclesiastical offices by

the king and by his vicar-general, who should have been convinced of

the guilt and unworthiness of such ministers, had they trusted their

own commissioners. In the case of some of the dioceses, as for example

Norwich, it is possible to compare the results of an episcopal

visitation held some years previously with the reports of Cromwell's

commissioners, and though it is sufficiently clear from these earlier

reports that all was not well with discipline, the discrepancy between

the accounts of the bishops and the royal commissioners is so

striking, that it is difficult to believe that the houses could have

degenerated so rapidly in so short a space of time as to justify the

Comperta of the commissioners. But what is still more striking is

the fact that after the decree of suppression had gone forth, other

commissioners, drawn largely from the local gentry, many of whom were

to share in the plunder of the monastic lands, visited several of the

houses against which serious charges had been made, and found nothing

worthy of special blame. These men were not likely to be prejudiced in

favor of the monks and nuns. They were well acquainted with the

people of the district, and had every opportunity of learning the

verdict of the masses about the discipline of the religious

communities. They were, therefore, in a much better position to arrive

at the truth than the royal commissioners who could only pay a flying

visit of a few hours or at most of a few days.

The real object of the visitation and of the scandalous reports to

which it gave rise, was to secure some specious pretext that would

justify the king in the eyes of the nation in suppressing the

monasteries and in confiscating their possessions. The idea that the

monastic establishments enjoyed only the administration of their lands

and goods, and that these might be seized upon at any moment for the

public weal, was not entirely a new one either in the history of

England or in that of some of the Continental countries. Years before,

Cardinal Wolsey, for example, had dissolved more than twenty

monasteries in order to raise funds for his colleges at Ipswich and

Oxford, while not infrequently the kings of England rewarded their

favorites and servants by granting them a pension to be paid by a

particular monastery. With the rise of the middle classes to power and

the gradual awakening of greater agricultural and commercial activity,

greedy eyes were turned to the monasteries and the farms owned by the

religious institutions. Unlike the property of private individuals

these lands were never likely to be in the market, and humanly

speaking a transfer of ownership could be effected only by a violent

revolution. Many people, therefore, though not unfriendly to the monks

and nuns as such, were not disinclined to entertain the proposals of

the king for the confiscation of religious property, particularly as

hopes were held out to the nobles, wealthy merchants, and the

corporations of cities and towns that the property so acquired could

take the place of the taxes that otherwise must be raised to meet

local and national expenditure.

For months before Parliament met (Feb. 1536) everything that could be

done by means of violent pamphlets and sermons against the monks and

the Papacy was done to prepare the country for the extreme measures

that were in contemplation. The king came in person to warn the House

of Commons that the reports of the royal commissioners, showing as

they did the wretched condition of the monasteries and convents called

for nothing less than the total dissolution of such institutions. The

members do not appear, however, to have been satisfied with the king's

recommendations, and it was probably owing to their feared opposition

to a wholesale sacrifice of the monasteries that, though the

commissioners had made no distinction between the larger and the

smaller establishments the measure introduced by the government dealt

only with the houses possessing a yearly revenue of less than £200.

Even in this mild form great pressure was required to secure the

passage of the Act, for though here and there complaints might have

been heard against the enclosures of monastic lands or about the

competition of the clerics in secular pursuits, the great body of the

people were still warmly attached to the monasteries. Once the decree

of dissolution had been passed the work of suppression was begun.

Close on four hundred religious houses were dissolved, and their lands

and property confiscated to the crown. The monks and nuns to the

number of about 2,000 were left homeless and dependent merely on the

miserable pensions, which not infrequently remained unpaid. Their

goods and valuables including the church plate and libraries were

seized. Their houses were dismantled, and the roofless walls were left

standing or disposed of as quarries for the sale of stones. Such

cruel measures were resented by the masses of the people, who were

attached to the monasteries, and who had always found the monks and

nuns obliging neighbors, generous to their servants and their

tenants, charitable to the poor and the wayfarer, good instructors of

the youth, and deeply interested in the temporal as well as in the

spiritual welfare of those around them. In London and the south-

eastern counties, where the new tendencies had taken a firmer root, a

strong minority supported the policy of the king and Cromwell, but

throughout England generally, from Cornwall and Devon to the Scottish

borders, the vast majority of the English people objected to the

religious innovations, detested Cromwell and Cranmer as heretics,

looked to Mary as the lawful heir to the throne in spite of the

decision of the court of Dunstable, and denounced the attacks on the

monasteries as robbery and sacrilege. The excitement spread quickly,

especially amongst the peasants, and soon news reached London that a

formidable rebellion had begun in the north.

In October 1536 the men of Lincoln took up arms in defense of their

religion. Many of the noblemen were forced to take part in the

movement, with which they sympathized, but which they feared to join

lest they should be exposed to the merciless vengeance of the king.

The leaders proclaimed their loyalty to the crown, and announced their

intention of sending agents to London to present their petitions. They

demanded the restoration of the monasteries, the removal of heretical

bishops such as Cranmer and Latimer, and the dismissal of evil

advisers like Cromwell and Rich. Henry VIII. returned a determined

refusal to their demands, and dispatched the Earl of Shrewsbury and

the Duke of Suffolk to suppress the rebellion. The people were quite

prepared to fight, but the noblemen opened negotiations with the

king's commanders, and advised the insurgents to disperse. The Duke of

Suffolk entered the city of Lincoln amidst every sign of popular

displeasure, although since the leaders had grown fainthearted no

resistance was offered. Those who had taken a prominent part in the

rebellion were arrested and put to death; the oath of supremacy was

tendered to every adult; and by the beginning of April 1537, all

traces of the rebellion had been removed.

The Pilgrimage of Grace in the north was destined to prove a much more

dangerous movement. Early in October 1536 the people of York,

determined to resist, and by the middle of the month the whole country

was up in arms under the leadership of Robert Aske, a country

gentleman and a lawyer well-known in legal services in London. Soon

the movement spread through most of the counties of the north. York

was surrendered to the insurgents without a struggle. Pomfret Castle,

where the Archbishop of York and many of the nobles had fled for

refuge, was obliged to capitulate, and Lord Darcy, the most loyal

supporter of the king in the north, agreed to join the party of Aske.

Hull opened its gates to the rebels, and before the end of October a

well trained army of close on 40,000 men led by the principal

gentlemen of the north lay encamped four miles north of Doncaster,

where the Duke of Norfolk at the head of 8,000 of the king's troops

awaited the attack. The Duke, fully conscious of the inferiority of

his forces and well aware that he could not count on the loyalty of

his own soldiers, many of whom favored the demands of the rebels,

determined to gain time by opening negotiations for a peaceful

settlement (27th Oct.). Two messengers were dispatched to submit their

grievances to the king, and it was agreed that until an answer should

be received both parties should observe the truce. The king met the

demands for the maintenance of the old faith, the restoration of the

liberties of the Church, and the dismissal of ministers like Cromwell

by a long explanation and defense of his political and religious

policy, and the messengers returned to announce that the Duke of

Norfolk was coming for another conference. Many of the leaders argued

that the time for peaceful remonstrances had passed, and that the

issue could be decided now only by the sword. Had their advice been

acted upon the results might have been disastrous for the king, but

the extreme loyalty of both the leaders and people, and the fear that

civil war in England would lead to a new Scottish invasion, determined

the majority to exhaust peaceful means before having recourse to

violence.

An interview between the leaders and the Duke of Norfolk, representing

the king, was arranged to take place at Doncaster (5th Dec.). In the

meantime a convocation of the clergy was called to meet at Pomfret to

formulate the religious grievances, and a lay assembly to draw up the

demands of the people. Both clergy and people insisted on the

acceptance of papal supremacy, the restoration of all clergy who had

been deposed for resisting royal supremacy, the destruction of

heretical books, such as those written by Luther, Hus, Melanchthon,

Tundale, Barnes, and St. German, the dismissal of heretical bishops

and advisers such as Cromwell, and the re-establishment of religious

houses. Face to face with such demands, backed as they were by an army

of 40,000 men, Norfolk, fearing that resistance was impossible, had

recourse to a dishonest strategy. He promised the rebels that a free

Parliament would be held at York to discuss their grievances, that a

full pardon would be granted to all who had taken up arms, and that in

the meantime the monks and nuns would be supported from the revenues

of the surrendered monasteries and convents. Aske, whose weak point

had always been his extreme loyalty, agreed to these terms, and

ordered his followers to disband. He was invited to attend in London

for a conference with the king, and returned home to announce that

Henry was coming to open the Parliament at York, and that the people

might rely with confidence on the royal promises. But signs were not

wanting to show that the insurgents had been betrayed, and that they

must expect vengeance rather than redress. Soon it was rumored that

Hull and Scarborough were being strengthened, and that in both cities

Henry intended to place royal garrisons. The people, alarmed by the

dangers that threatened them, attempted vainly to seize these two

towns, and throughout the north various risings took place. The Duke

of Norfolk, taking advantage of this violation of the truce, and

having no longer any strong forces to contend with, promptly

suppressed these rebellions, proclaimed martial law, and began a

campaign of wholesale butchery. Hundreds of the rebels, including

abbots and priests, who were suspected of favoring the insurgents,

were put to death. The leaders, Aske, Lord Darcy, Lord Hussey, Sir

Thomas Percy, Sir Francis Bigod, together with the abbots of Jervaux

and of Fountains, and the Prior of Bidlington were arrested. Some of

them suffered the penalty of death in London, while others were sent

back to be executed in their own districts. By these measures the